Grieving is Mythmaking

AAA games rarely deal in the tragicomic mode when grief is a major theme. Mainstream games often privilege narratives and scenarios that center a player’s sense of empowerment. This gives them less space for the absurd or funny. I believe this phenomenon is a detriment to game narrative design’s potential because grief isn’t always a straightforward or galvanizing experience. If a game wants to engage with themes of grief, it usually does so in absolutes and epic metaphors a la Shadow of the Colossus. And if a game includes both tragic and comic elements, they are dealt with in isolation. Likely this design strategy is to preserve some modicum of levity such as with The Last of Us series. There are exceptions, of course, like Ni No Kuni: Wrath of the White Witch (more on this later).

Compartmentalizing different emotional states (and the mechanics and systems that could represent them) leaves a lot of nuance left unexplored. To the Moon, Brothers, If Found, Dordogne, and Zau:Tales of Kenzera may not necessarily be characterized as tragicomic, but all titles offer ways that games can explore grief without excluding other related emotional states like generational catharsis, gender euphoria, and camaraderie in the midst of grief. In fact, I’ve generally found that a sincere tragicomic tone is explored more in AA and indie titles like the aforementioned. Such projects are more often personal and aren’t driven by the impetus to snag a broader audience.

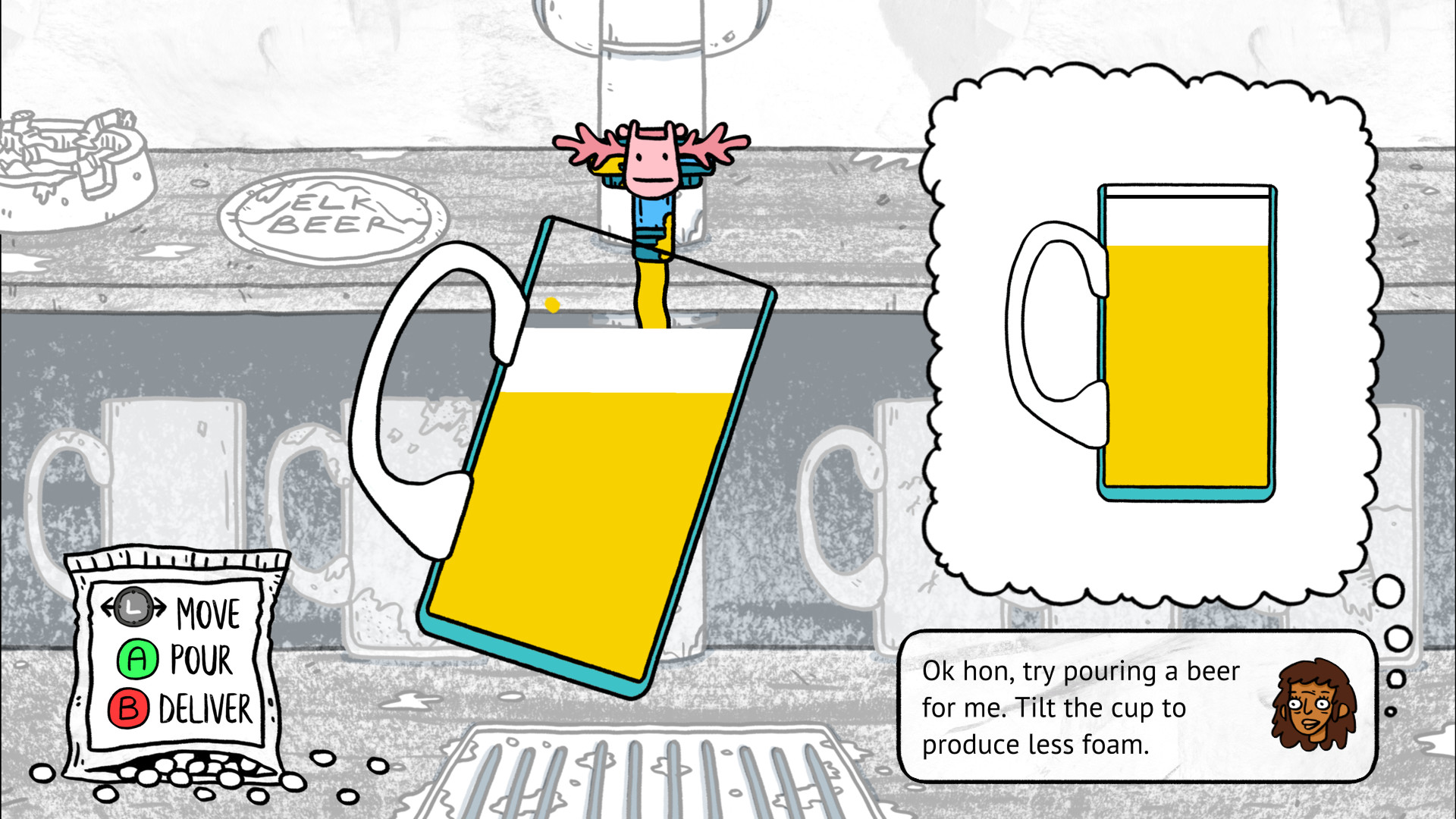

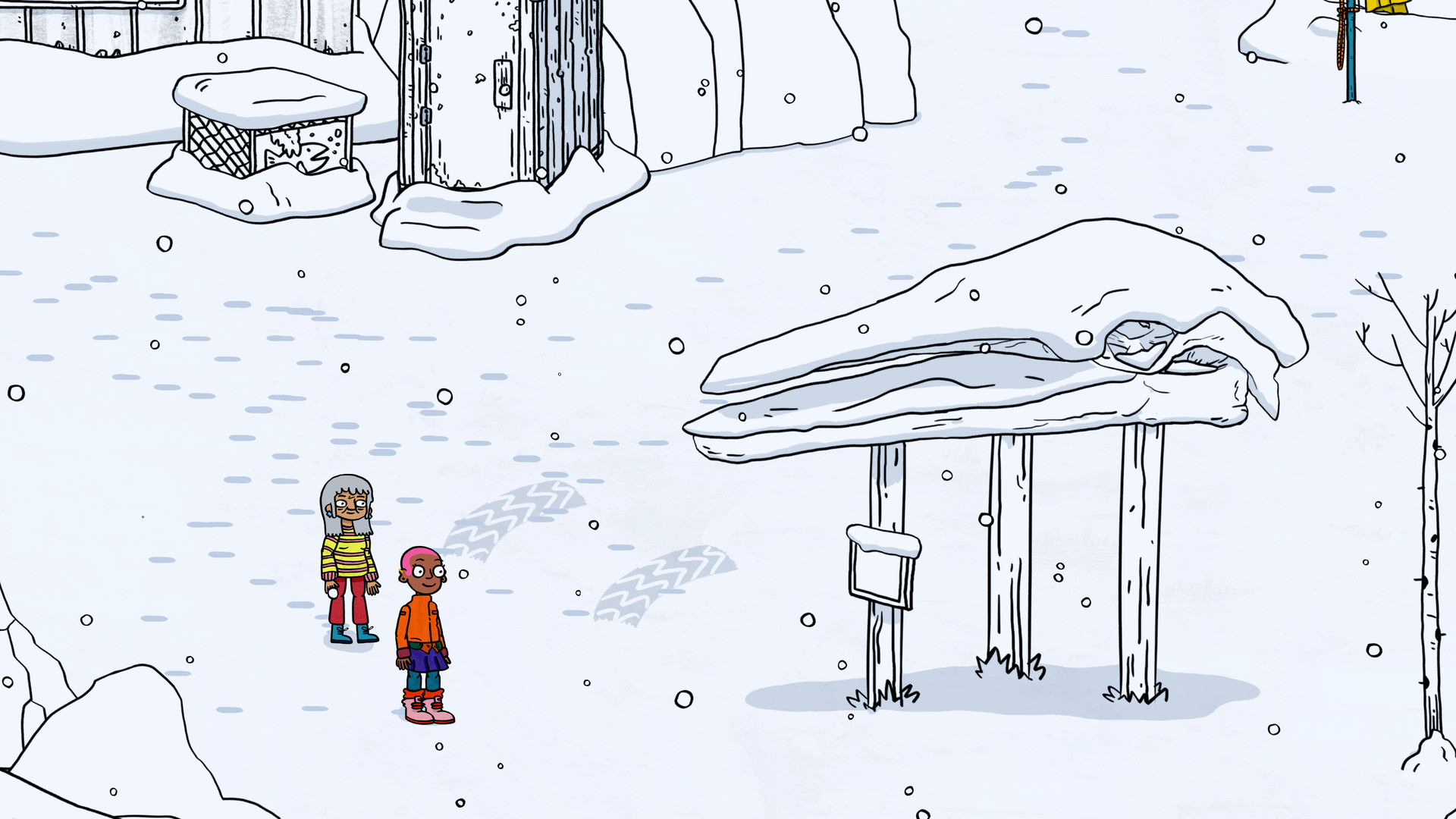

Triple Topping’s biographical game Welcome to Elk fits this category of games which tackle grief in a nuanced, if sometimes unorthodox, way. As several critics have noted of Elk, despite the subject matter being heavy, including poverty, alcoholism, sexual harassment, child abuse, death, the game doesn’t feel mired in the inherent gloom of these traumas. Instead, its intermingling of lighthearted minigames and serious documentary-style interview clips express equal amounts of frivolity and sobriety (sometimes literal sobriety as player character Frigg and others deal with the aftermath of going on benders). The game is free to explore grief in an experimental and intertextual way, since it’s an indie project funded by the Danish Film Institute’s subsidy for Danish game development and production.

Grief as an emotional state is in fact multifarious, connected to many different actions (both passive and otherwise) and can take many different forms externally and internally. As the introduction to Sloane Crosley’s recent memoir Grief is for People describes, sometimes our experience of the grieving process is unorthodox, putting the “Container first, emotion second.” In short, processing grief and becoming more resilient to it takes on different patterns or requires unique methods or systems. Perhaps that’s why games tend to characterize grief as an epic journey, something that can gather everyone under a sort of universal narrative of the experience. But Welcome to Elk wants to focus on how grief is as much about its individual framing as it is about our path forward (or backwards or sideways) from it.

Grief is mundane, despite how profound of an emotion and process it is. Grief can also be cumulative, collective (or both simultaneously) and Welcome to Elk is adept at illustrating this. Think of the bottles containing the handwritten true stories of the island’s daily events that slowly commandeer player character Frigg’s dining table. Her mounting discomfort towards these artifacts’ mysterious appearance, visions of oral storytellers and the island’s communal dreaming about the afterlife are all tied to mundanity. The latter two may sound more disconnected from reality, but are grounded by said oral storytellers being relatives of the game designers. As well, the communal dreams seem to be triggered by consuming alcohol at the local pub. Sometimes the game highlights the cumulative nature of grief in a literal sense, however, with some of its more madcap minigames.

For instance, Frigg mini-golfs with a rich man’s inherited junk in one act while in another she’s recruited to build an elaborate contraption out of scrap materials for a single mother to hunt local wildlife for food. As Grace mentioned in her close-reading of the minigames, one of the more impactful ones has Frigg stitch together an islander’s head wound using a fishing hook. Then there’s the charon-like boat being slowly constructed throughout the narrative, which traverses both the waters of Frigg’s troubled dreams and the sea beyond Elk island in the concluding act. This boat also brings her in touch with the Triple Topping studio and the tellers of the true stories, which inspire the game’s narratives of grief, crossing from interactive fiction fully into behind-the-scenes documentary. Some minigames do feel more incidental than anything, like Frigg learning to perfect pouring beer, but I liked the mix of commonplace and weird experiences. Although this mix didn’t always cohere with the game’s themes, the disparate tones highlight the overlap of the habitual moments with the mythical symbols of grieving.

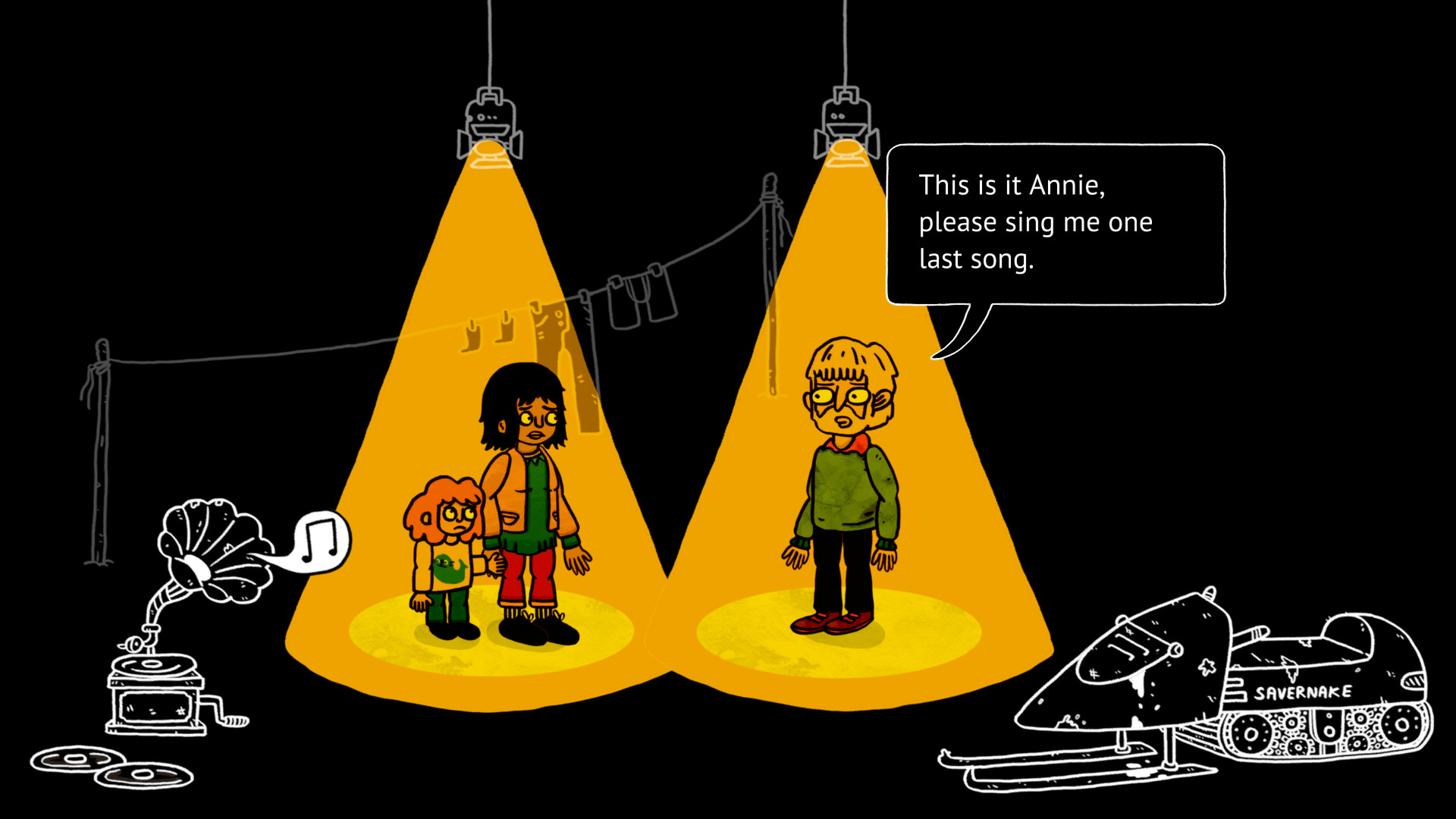

The aesthetic of the game is easily one of its most memorable aspects. The felt tip, zine-meets-children’s book visuals and its folksy alternative music are second only to the game’s usage of several different forms of storytelling, ranging from environmental to ludic and even cinematic. All elements of this game stress a DIY philosophy of dealing with the limitations of Elk’s isolated Nordic island life. The minigames are also bespoke to each individual character dealing with their personal grief, from singing to the aforementioned mini-golfing with assorted junk to even fishing for sunken beer bottles. There’s something of the discourse between what anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss believes defines someone as a bricoleur and an engineer in the game’s procedural rhetoric, or the way it persuades players via mechanics of its themes of grief and resilience.

Levi-Strauss believed that mythmaking or finding meaning was, for a bricoleur, an act of creation or bricolage (derived from the French term for tinkering, bricoler) using the materials they had at hand. An engineer by contrast was the role model a bricoleur would emulate, a craftsperson who tackles mythmaking projects completely and creates new tools specially for that purpose. Jacques Derrida, the philosopher who developed deconstruction theory, critiqued the inherent high and low culture distinction between the figures of bricoleur and engineer. Levi-Strauss characterizes the former as a mythmaker deriving from the latter’s scientific and self-contained discourse. Derrida posits that since no one is the “absolute origin of his own discourse”, technically the engineer is an ideal myth invented by the bricoleur. Most people then, are mythmaking bricoleurs, inspiring each other with cross-pollinating ideas and using materials accessible to them to make meaning out of everyday experiences.

This is certainly the case for Welcome to Elk’s procedural rhetoric. Nearly everyone on the island, save maybe Leeroy and the Sheriff (both figures who are more concerned with controlling people or information) is a bricoleur with an attendant minigame about making meaning out of everyday experiences, using what’s at hand. Early in the game Frigg is asked by the town eccentric, Anders, to show him what his late parents must’ve looked like. Since Frigg isn’t an orphan like him, he reasons, she must know how to identify parents (as if they are monolithic beings). The minigame has you collaging cut-outs of eyes, noses, and mouths on balloons. Anders coaches you on vague qualities he believes his mother and father must’ve had so that he can understand how to find and meet them finally in the afterlife. This use of bricolage is central to Welcome to Elk and its way of conveying, as Michael Iantorno posits in his essay, the resilience of an isolated community. As well, it’s a striking aesthetic for the themes of cumulative and collective grieving mentioned above.

This rhetoric even includes the developers (arguably more alike to the engineer) whose voices break the fourth wall in one act problem-solving technical design for one of the more somber minigames, where Frigg must help Jan carry a corpse to a sled. Frigg questions her companions about overhearing the discussion, but they seem oblivious and dismissive of the occurrence. This event definitely puts the game squarely in Derrida’s camp regarding the engineer who creates narratives totally in isolation. Triple Topping may be physically outside Frigg’s fictional existence, but they are psychologically tied to her as she is their vessel for witnessing and making sense of the tragic true stories of Triple Topping’s relatives.

As mentioned above, Ni No Kuni is one AAA title that handles grief in a similar manner to Welcome to Elk, with tragicomic overtones and mythmaking. Oliver, who recently lost his mother, accesses parallel worlds via everyday materials imbued with his intentions. Oliver’s tears bring to life his companion Mr. Drippy, who was previously an unassuming doll sewn for him by his late mother. Drippy instructs the boy on how to become a wizard who can travel to the mythical Other World from his modern one of Motorville. He does this by using a “stick-like” object for a wand and a book found in a fireplace for a grimoire. By focusing on his intention to find his mother’s soulmate (a person or being from Motorville’s spiritual parallel), a great sage named Alicia, in Other World Oliver can traverse there. Most of the wizardry in the game is also based around the exchange of emotions as well. If one were to take away the literal representation of Other World, one could simply frame Oliver as a child playing pretend to engage in some lighthearted escapism as he moves through the stages of denial and bargaining to eventual acceptance of his grief over losing his mother. Indeed, when Oliver returns to Motorville from his first foray into the Other World, people comment on his wizard outfit as if he is merely playing dress up to cope with his mother’s passing.

Welcome to Elk, like Ni no Kuni, emphasizes the absurdity of both individual and communal grieving, seeking to express the ways one attempts to restore a sense of normalcy and control to daily life via storytelling. That’s why there’s such an emphasis on how storytelling, whether of true or tall tales, is held in such regard on Elk. The key differences between Elk and Ni no Kuni, however, is that Elk’s more speculative aspects aren’t as explicitly stated. Unlike Oliver, Frigg can only witness and facilitate healing for the other characters by carrying these stories with her. Oliver’s mythmaking is made more explicit and he is an agent in his story of grief, traversing worlds, restoring order, and arguably using his nostalgia to resolve his grief.

Triple Topping’s game is concerned particularly with the boundaries between the triggering events of grief and the narrativizing of that emotion in the aftermath of them. I do agree with Iantorno as well that the game’s intertextuality also underscores the limitations of games to capture the nuances of political stratification and grief. But above all, what stuck with me from my time spent on Elk island was the notion that, while we all have our individual journeys of grieving, we are interconnected by the way we use our mundane settings and experiences to find a path to accepting our grief.