Missing A Stitch

The humble minigame can be written off as a distraction, but in my mind it can be as potent as anything else in a video game. Shenmue still has the most evocative minigames, because it gets closest to the real texture of life. You have a couple hours to kill before a bar opens, so why not stop at the arcade or race ducks in the alleyway? Obviously, we can engage in a game deliberately, but often we play out of idleness or sheer twitchy sensation. Shenmue takes place in the shadow of grief, which grows all the more poignant because of how the rest of life just goes on. Even in the valley of the shadow of death, you can just waste time.

Welcome to Elk aspires to span a similar emotional space. As protagonist Frigg encounters the various inhabitants of the town, and island, of Elk, she is apt to find a minigame or two, in between antics or sorrowful stories or tense drama. Most of these minigames are silly. In one, you play minigolf with an eccentric rich man in his backyard and it turns into a miniature What The Golf?, in which you use beer bottles and flags as golf balls. In another you build convoluted squirrel traps with bouncy balls, springs, and slides. This playful tone is intentional as Welcome To Elk plays with the space between regular life and dreams. However, I found that the games took me out more than they drew me in.

Don't get me wrong, I have more than a little affection for the madcap absurdity of a Mario Party minigame or the frantic confusion of Warioware. My objection is not that Welcome To Elk's minigames are silly, but that I don't know how they give texture to the game's grounded, if dreamlike, setting. One karaoke minigame has you essentially write little four-note melodies that get echoed by a duet partner. This doesn't resemble karaoke, especially not karaoke using a busted up old machine on a rural island. The music sounds like a rightfully-forgotten The 1975 b-side, rather than the corny pop you are more likely to find on such a device. Yakuza's (or Like a Dragon's) karaoke is beloved not because it is a compelling rhythm game, but because it communicates something about the emotional spaces of its protagonists. When Kiryu sings the rocker "Judgement" or the plaintive piano ballad "Bakamitai'' in Yakuza Zero, it is expressive, narrative. In Welcome To Elk, the karaoke is somewhat expressive, but doesn't tell me anything about this island or these characters.

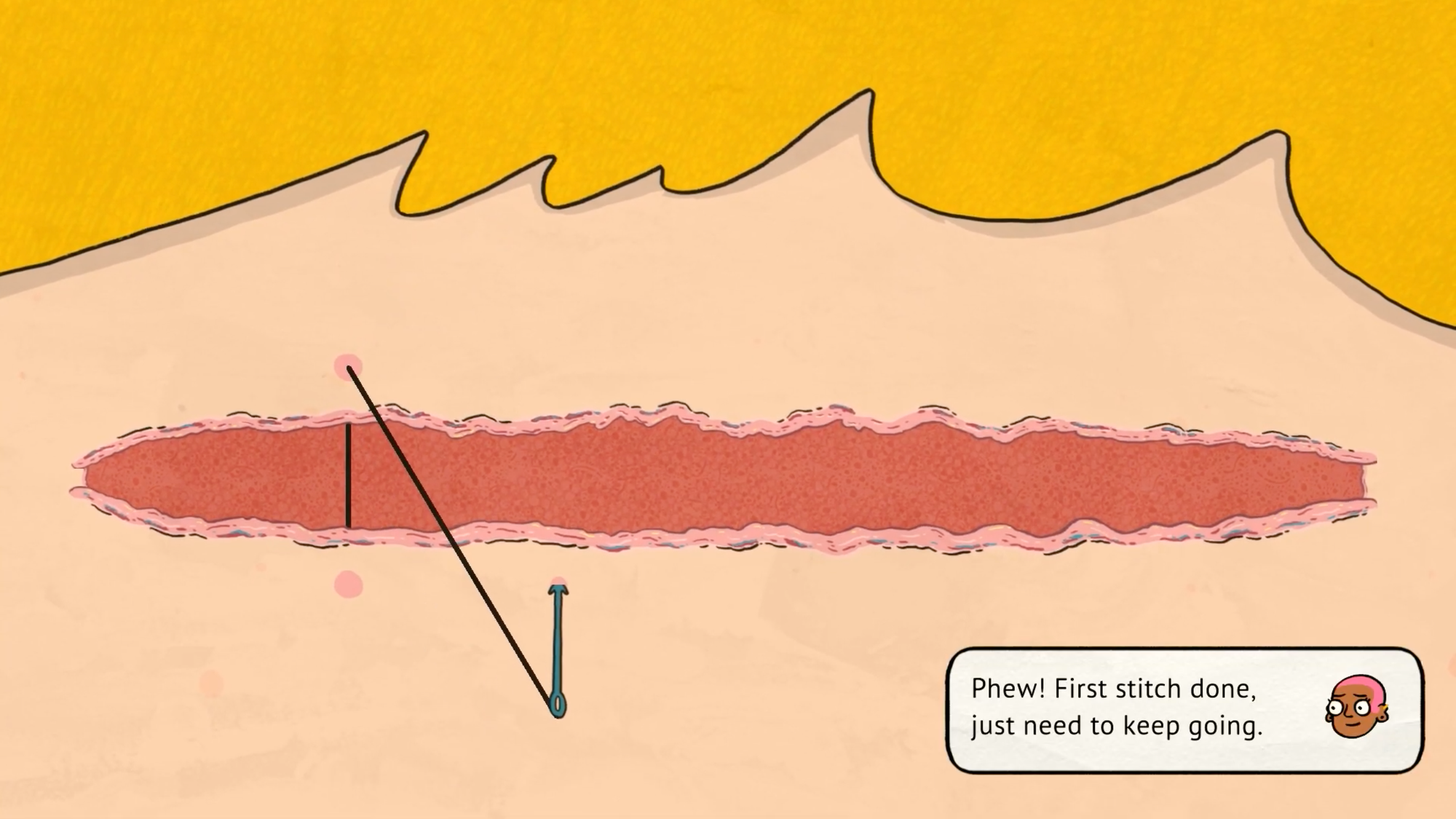

Fittingly, the most effective minigames in Welcome To Elk are the grimmest of them. Carry a corpse out of the hostile, cold air. Stitch together a head wound with a fish hook and fishing line. Deliberate over who should, and how they should, kill an ailing pet rabbit. Because of the subject matter, there's absurdity and even a dark humor, but these minigames are unadorned and unpretentious. They rely on their context to provide emotional impact and depth. The one where you carry a corpse essentially turns into a cutscene, but you have to keep pressing up on your thumbstick for it to continue. It depicts a horrifying moment when you are desperate to look away, but must look, must continue walking, in a time that feels like forever. It is when the game considers death, or panic and fear, that it feels closest to real human complexity.

Of course, I don't expect other minigames in Welcome To Elk to carry that sort of emotional heft or range. What I do expect them to provide is a clear sense of texture. Elk island is made out of real world stories, told to the developers by relatives and friends and acquaintances. There is a sense of reverence around these stories, even when they are absurd, funny, or marginal. These tonal switches sing because they are wound up in regular living. Too often Welcome To Elk's minigames feel like interruptions rather than continuations.

Welcome To Elk has a little bit of Pentiment in it. Both concern outsiders in relatively isolated communities, both have surreal dreams featuring boats. Welcome to Elk made me appreciate how bare the minigames in Pentiment are. There is not really any elaboration or gamification. They are simple. The focus is directly on texture alone. Pentiment’s minigames never get cute, and through that it lends its setting a tangible dignity.

Welcome To Elk has that dignity in spots (one simple card minigame game at a party sprang to mind), but squanders it too. After all, What the Golf? is an amusing distraction. Its virtues are best shown in a social media timeline. It can get laughs, but it cannot be pondered or dwelt in. This is not just because it is irreverent or slapstick, but because there is so little beyond the gimmick. Welcome To Elk's turns itself towards artificiality, but also towards a groundedness in a particular time and place and in the particular people that inhabit it. When Welcome To Elk's minigames swerve into indie game homage or broad absurdity, we leave that world behind to be distracted for a while. Even a humble minigame can do better.