Parun's Quilt—Poems in the Patchwork Collage of RPG Maker

"It hurts so much, but this is all for you

I write a letter to you in my red blood"

- Translation of lyrics to "Fushigi Na Shiawase" (Mysterious Happiness) by NejiP feat. Hatsune Miku

- From the soundtrack to RE:Kinder (2010) by Parun

RPG Maker–released in Japan as RPG Tsukūru by ASCII/Enterbrain/Kadokawa Corporation–sometimes has a negative connotation of only producing “RPG Maker games”, referring to how the end results look “samey” or “amateurish”. Compared to the more blank canvas-like approach possible with engines like Unity, Gamemaker, or Godot, RPG Maker would often be considered less versatile in bringing a wider variety of ideas for mechanics and aesthetics–the commercially acceptable kinds, anyway–closer to a uniquely realized form. Yet any common ground in the craft of games made in these engines, as professional products or to otherwise appear “respectable”, can be more difficult to glean. Much of the time, games from these engines exist as if each were birthed from the ether, providing less evidence within them of some greater identity to tie them to. The Unity “asset flip” would be sneered at partly for a perceived lack of individual identity, yet games that aim for distinctness often hide the methods of creation that they shared with their siblings. The player cannot intuit a common, material history between these works that wish to appear individual unto themselves. And so, without outside context, each game stands isolated, alone.

Em Reed, speaking on game engines, notes this as a symptom of how “professionalization of the industry has tried to make process invisible, and present the videogame as a slick, black-boxed toy.“ With the context of the process left unseen, language is put forth in this vacuum around games as a matter of developers making “objectively” good or bad design decisions consciously. This language would be exploited by the corporations that distributed these “indie” engines, the minority of breakout careerist “indie” developers positioning themselves as figureheads, and various other “indie” proselytizers to justify commercial ideology around games as product. Despite much ado about these engines “democratizing” tools for making games outside the mainstream, “indie games” itself is ultimately, as Reed says, “[a] classification [which] was not something outside of corporate centralization, but working alongside it.” Games trying to elevate themselves through their aesthetic pseudo-individuality, to lay a claim as being “higher” art, only obfuscate their relationship to the industry they are part of, furnishing themselves as product. “Indie” has become an industry itself, upholding established and entrenched values familiar to and of the mainstream rather than truly changing the means by which games are made and how they are discussed critically.

While RPG Maker is not exempt from criticisms of playing into the “indie” industry itself, what its games are commonly derided for ought to be considered for how they counter fabricated industry standards around “legitimate” art. The basic mechanical uniformity found in RPG Maker games has its roots in the developer’s intent for the software as a means for its users to create top-down fantasy RPGs, in the tradition of Final Fantasy or Dragon Quest before their move to 3D. RPG Maker's built-in default assets leaned into genre expectations of these 16-bit RPGs with swords, dungeons, magic, and the like (with ones based around science fiction or contemporary settings also in the mix, if you’re using later versions of the program), and the software did not easily allow extreme deviations from how these RPGs usually play. These generic qualities, as interpreted by RPG Maker, set clearly defined limitations and strict patterns to follow for game creation. It was a framework encouraging variety and experimentation not as much with form as with content.

Alongside how they are made to play, the visual aesthetics of RPG Maker games were subject to the rules the engine set for how to arrange tiles, sprites, and various UI elements. But the engine did not force what these elements were, as those who did not want to only use the default assets had the option of importing new ones. Creating custom sprites, tiles, music, etc. from scratch was a valid option but, even as it would be valued as giving “original” touch to RPG Maker games, it was not something every user wanted to invest the time in doing for the entirety of their project. The alternative option was to import and edit images and music found off the internet to be used as graphics or a soundtrack. Especially early on in the international scene, this meant stealing them, a practice RPG Maker would be notorious for early on. Licensed music and sprites ripped from commercial games were common targets, whether used for fangames taking assets from their respective inspiration or as part of a mishmash of images from anime, film, photography, etc. to be reinterpreted in the world of some dev’s passion project. Long, storied chains of stealing occurred as users took assets and techniques from other games for their projects, which themselves could be stolen from mysterious outside sources.

The widespread remixing of copyrighted assets was spurred on by Don Miguel's illegally distributed English translation of RPG Maker 2000–for many years, the only means for those outside of Japan to use the program. The “pirate ethos”, as Reed puts it, of using illicit software to make illicit games meant “users [were] not simply corralled into normative, desirable production…[but allowed] to take apart and rebuild the locked down, black-boxed video game in new ways.” This culture of theft was stalled (though exceptions are out there) with official English translations of future versions of the software and cease-and-desists from corporations handed out with more frequency, but it still stands as a radical and highly legible moment for the engine’s transformative potential. The re-interpretation of these commercially distributed images and sounds, each with immediate, widely understood context behind them to begin with, served as a loud example of the tendency of the engine to thrive on re-interpretation in general. Logically sensible aesthetics could be eschewed for the mix of chunks of disparate contexts, legally obtained or not, placed together under the framework of the engine and creating present narratives on top of past ones.

RPG Maker games’ distinct character, then, are as patchwork collages. It was patchwork for the variety of materials—each with its own inherent, individual context brought to the whole—and it was collage for how these already-contextualized pieces could be placed in an immediately recognizable means to engage with the whole. It wasn’t that the games shared a coherent quality from their individual elements, but that they had familiar patterns that emerged from these elements’ arrangements. A user could evoke something personalized out of the engine’s built-in material, or whatever material they gathered or created themself, not solely guided by ideas but by feedback from the process itself. This implied a de-emphasis on conscious intentionality in games-making, contradicting a mainstream and indie ideology that dictates commitment to vision, and utilization of specific skills, as the only path to making “real” and “artful” games. The engine asserts itself without regard for having to be anything else, its legacy evident in the push and pull of its process, and the feel of its games anyone can look at and say, “that’s an RPG Maker game.”

Parun, working in RPG Tsukūru from 2002 up until his death in 2010, would harness the engine’s patchwork collage qualities in his reuse of material made by others, using default assets as is or making edits to them, and sometimes adding his own art into the mix. He wasn’t going so far as to skirt around copyright with the whimsical abandon of much of the early scenes outside Japan, as he gave credit in his games for where he got his resources. These included sites for Tsukūru-specific graphics that were freely available for anyone to take for their projects, implying some form of community culture for sharing assets he took part in. He also used music, sounds, photography, and artwork from online sources that were either public domain or otherwise available for non-commercial use, such as various paintings and music from other free games. Even if standards around sharing varied from scene to scene, he was clearly engaged in a general culture of recycling and reappropriation that generally existed in both the Tsukūru communities of his country, as well as the RPG Maker ones outside of it. There was seemingly little concern for being “unoriginal” with assets, as it was implicitly understood by him and many other RPG Maker/Tsukūru users that, in making games for free, you could reuse whatever you could find that was reasonably available to you. He used the assets he used likely because they were available to him, relevant to the subject of his game, and able to be adapted into the quilt he wove.

Though to say his approach was purely utilitarian did not account for how he would eventually interweave his asset use with the themes in his games that were always personally guided. His early RPG Maker works, even as blunt “social message” stories, were consistent with this drive: kinder was a horror game set in a world where mental illness is not recognized medically or treated as real, and If… had you play as a disembodied being exploring a society where straight people are stigmatized and being gay is the norm. Both deal in subjects directly important to Parun as a queer person dealing with mental illness, but in comparison to his later work, they can feel overly simplistic and non-specific in framing. They were also more didactic in “explaining” the particular facets of gayness and mental illness they dealt with, as if to make these identities easily digestible and non-provocative. It would make some sense, considering these games were put up for a general free game audience that was largely assumed to lack experience with, or exposure to, what’s outside a heteronormative and neurotypical viewpoint. But this approach doesn’t make them particularly engaging as personalized works.

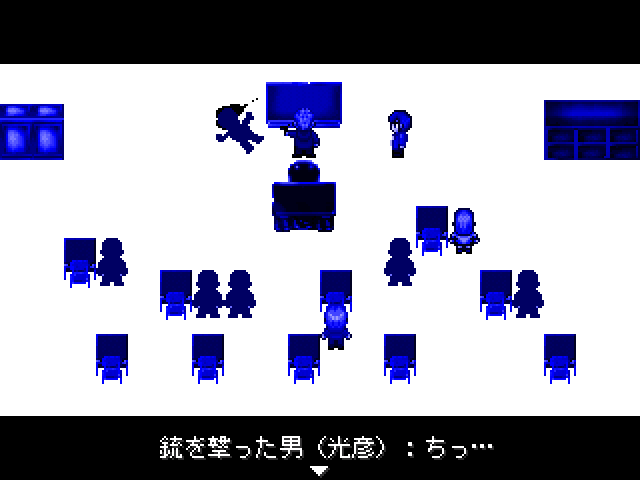

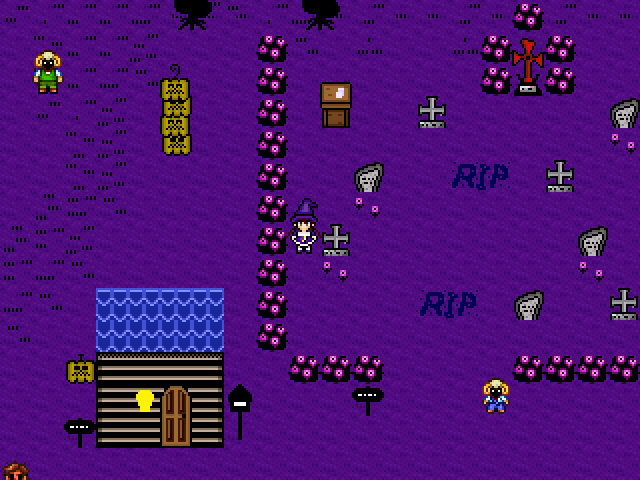

Still, a desire to challenge this audience and express something singular to him would become clearer to see within his games over the years, as he developed more nuanced and stylized methods of expression in the engine towards this end. In a few years after the more comparatively conventional kinder, Mitsu to Ageha (Honey and Swallowtail)’s empty, negative space backgrounds for white and blue monochrome tileset edits would give it its noir-ish feel, suiting its story of violence and abuse and interpersonal communication through the internet. Not long after, SWEET HALLOWEEN’s more adventurous mechanics would depict a sex work metaphor; collecting children’s screams to make candy for adults and then evading the police, all wrapped in the spooky-cute sweets wrapper of its graphics (admittedly the most visually “coherent” of his games). Both showed a more focused consideration of reused, original, and default assets for setting mood and tone, but they were also comparatively coherent in their arrangements, a quality he would gleefully abandon in his two larger scale RPG Tsukūru games to come.

Following 15 months after SWEET HALLOWEEN, Heisei Pistol Show would mark a significant moment in Parun’s gameography, one with a clear before and after for his fixations as an artist and how to communicate them with greater ingenuity and specificity. This title is also the one with the clearest autobiographical bent: as Parun writes in a blog entry, Heisei Pistol Show was initially created to mock his ex he recently broke up with, but he began to soften his view on him as he reflected on himself. It is this desire to re-examine the past that contextualizes not just Heart and Matsumato’s perspectives on each other in the story contained to the game, but the craft of the game that contains it. Heisei is both a meditation on the collagic process of RPG Tsukūru as Parun has come to understand it, as well as a culmination of his own history of expressions with the engine up to that point. As a work thoroughly defined by re-interpretation, the patterns of the engine and the variety of material Parun brought to it would themselves become subjects of this retrospective investigation.

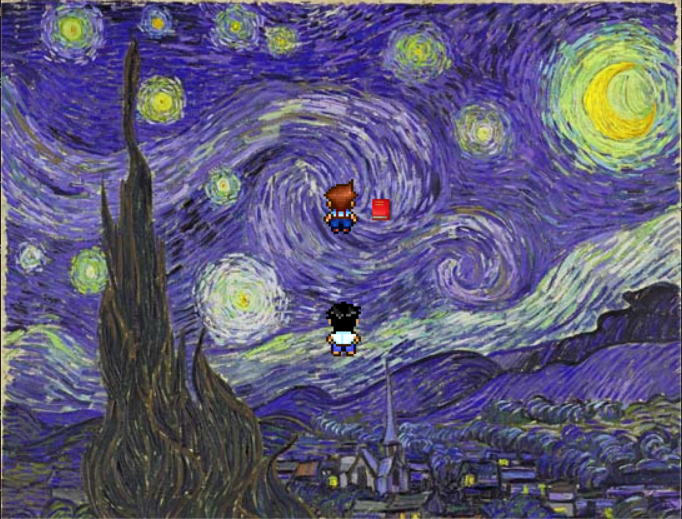

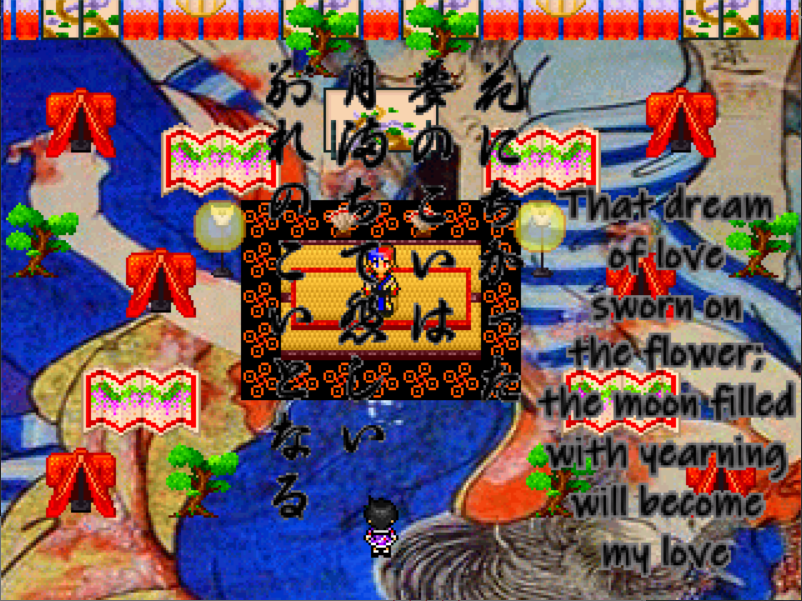

The world of Heisei is dissonant in space, time, and meaning, with the underlying structure of RPG Maker keeping it intact for the player to explore. Exiting a cyberpunk city area one way could jarringly lead to a mirror version of it with negatively inverted colors, another exit inexplicably going to a lava dungeon room of a classical RPG, which itself is next to a temple with a pre-rendered look out of nowhere. Heart commentates with a narrative he makes up for each map you enter, assigning self-made history and intention to what would seem to have none. Similarly, Heart changes the lyrics for Twinkle Twinkle Little Star, a well-known nursery rhyme and almost theme of the game, every time he sings it. In placing these maps and music assets taken from different sources in this jumble, without immediate sensical continuity between them, Parun disrupts the inclination to take the game world as an unobtrusive background for the adventure. Each map, sprite, and object is put forward as a distinct surprise to happen upon, begging the question of why it is as it is. Parun’s answer is simply to do as the protagonist does, making up a story and lyrics as he goes along. To infer relationships between these disparate elements, positioned to contradict each other because it entices interpretation.

Not only does this lend to interpretation within the narrative, but it points back to RPG Maker’s process and the nature of its materials. The lava map or the cyberpunk map, freed from the confines of “making sense” for a fantasy RPG or a sci-fi story respectively, become recognizable as simply maps for use with RPG Maker. Music that does not feel like an RPG backing track (until it is), or otherwise contrasts against the mood of a scene, similarly brings attention to itself. The fact comes up that these assets were made by someone, by some intention or process that may or may not be lost to us, to be shared in all kinds of games or projects. Heisei chooses to let the context of its found assets speak for themselves, highlighting the history or potential history behind them, rather than chaining them together exclusively to an author’s vision that hides their histories from the player. With this honesty in pointing at the patchwork bits that color its flesh, the structural skeleton of the engine underneath is revealed; Heisei, even as a mess of bits and pieces not beholden to any ideals of singular aesthetic, still sings in a language and grammar that anyone can potentially understand and use themselves.

Much of the material that Parun used to build the world wasn’t just freshly gathered assets, but ones he had previously used in his games up to Heisei (the majority of which themselves would have been gathered from these sites in previous years). Foreknowledge of his previous use of the assets calls attention to them, and assigns them a special intent on Parun’s part left to the player to interpret, as is understood with the associative nature of the rest of the game. Take the glitched looking city street from If…, or the corpse of SWEET HALLOWEEN’s protagonist Lily in a familiar graveyard, or the reuse of silhouetted bodies with brains blown out from Mitsu to Ageha for victims of the pistol that all come back in Heisei. All become more than assets re-borrowed for utility’s sake, but signifiers of ideas he was playing with in those previous games–to find new meanings out of these memories within the present. This intertextual approach with his own oeuvre gave Parun a means to lay his own stake into material that was not always made by him, but that he could attach a new significance of his own to (not unlike the stories of oiran he draws upon, relating them to the context of queer sex work). It’s not that Parun justifies reuse, as it does not need justification, rather by imbuing these shared objects with symbolic power of his own, it further points back to a history he shares with and through other developers that had designs in adapting, or initially creating, these objects.

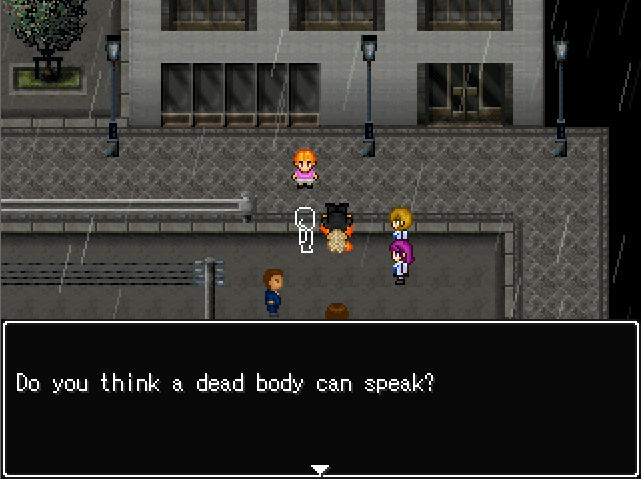

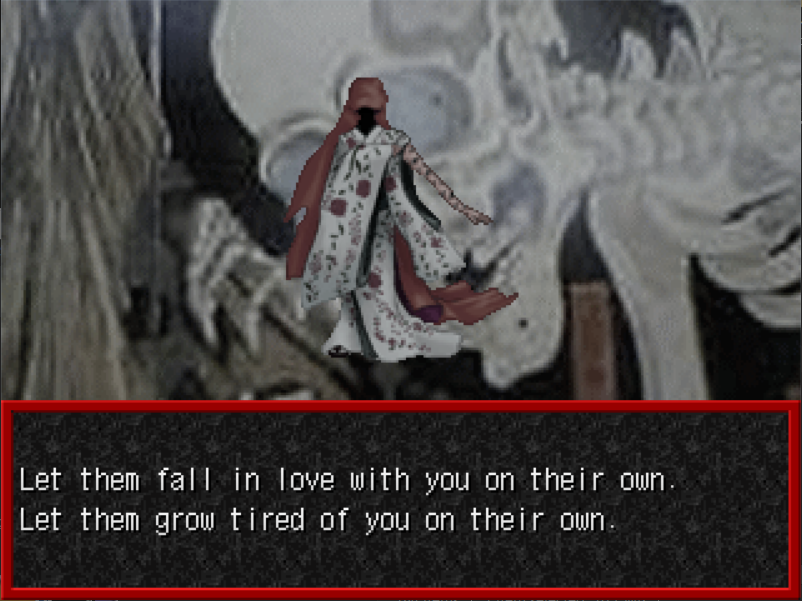

Parun’s final game, RE:Kinder, would continue his contemplation on his past work and the preoccupations within. It was a 2010 remake of 2003’s kinder, his best known and most ambitious work up to that point, and the one that most aligns with a more conventional RPGMaker horror structure of games like Corpse Party and GU-L. Unlike Heisei Pistol Show’s variety of isolated references to many of his previous games through asset reuse, RE:Kinder’s retrospection is more focused to, and more exhaustively drawing from, two of his games: kinder and Heisei. Most of the plot and characters come from the former as a textual foundation, and the style, motifs, and themes Parun developed in the latter are inherited by RE:Kinder. Black humor, moments of capricious theatricality, and the more thoroughly queer signifiers found in Heisei are situated against the more morose, self-serious nature of kinder, as a horror story of child abuse, mental illness, and generational trauma. Both exist in a thorny yet rosy-colored dialogue with each other; Heisei works as Parun’s scampish present self at that point in time, and kinder as his more taciturn past, a back-and-forth dialectic by which he re-interprets his history in the now.

Remakes of RPG Maker were at least contemporary to RE:Kinder's release if not preceding it, even as remakes would become the more ubiquitous (and contentious) trend they are these days. A common practice with RPG Maker remakes, continuing to the present, is to use a more recent iteration of the engine, for greater flexibility in visual detail, scripting, etc. to expand past the limitations the original worked within. Cases like Corpse Party -Rebuilt-, fan-made in RPG Maker XP from the PC-98 only Dante 98 version, or the 2022 version of Ib, made in RPG Maker MV to be sold commercially following the freeware RPG Maker 2000 version, all share this tendency to stick to the engine. Yet many of these RPG Maker remakes may make the switch to, arguably, work in a “better” engine with the idea of “improving” their original game, as if a work can inherently have or gain some sort of deficiency to be “corrected” in a new version. Or, conversely, the remake may be held by an audience, or other production forces, to standards of “faithfulness” to that original, constraining some potential vision it may have as a work its own sake. It’s within the ideology around commercial game development, and its tendency to conceal artistic process, to value “optimization” in remaking works of art. Instead, critics should understand both an original and its re-interpretations on their own terms, and through their distinct development contexts.

Parun’s choice to bring kinder from RPG Tsukūru 2000 to its VX iteration was also to take advantage of the new engine’s features, yet RE:Kinder expresses something going beyond “optimization”. One example is with VX’s default tiles, which are arranged to create the exterior and interiors of Kowada Town in RE:Kinder. The original kinder’s modern setting was only possible through gathering assets for the look he wanted, as RPG Tsukūru 2000 more strictly leaned into fantasy settings. The default tiles in VX would save him the trouble of looking for ones that fit, but the use of these defaults also signified how Parun approached VX as a toolset that was ontologically similar to 2000 in many ways, yet fresh with possibility. As his first game in the newest iteration at the time, he created maps that would appear to be modestly simple arrangements with the built-in tiles–at times frowned upon as amateur’s material–but then edited or otherwise given some twist that comes with prior RPG Maker experience. Keeping the exact same sprites from the original kinder too, set against the more detailed and plasticine-looking environs, should be considered not just for ease’s sake but for what the juxtaposition in those elements can imply. RE: made the engine version change, a common strategy in RPG Maker remakes, into a site for a vivid collision for Parun between pieces of his own history with a new, though undeniably familiar, world of possibilities to play within.

Yet ever present in this freshly re-created town, always visible in the parallax background between buildings, is a pattern of roses recalling Heisei. This background element serves as a thematic reminder of the present reasserting itself in the past; a memory cannot be revived crystallized in the context of its time, but must contend with the present that calls upon it. A decision like this, and others like the out-of-left field cutaway gags, or the fable of princesses and their princes (lifting what was previously gay subtext almost fully into text), all are clear divergences from the original kinder with a freewheeling, subversive aim. These show Parun did not think of RE: as a straightforward improvement of kinder, or as something needing the proper amount of reverence to that original work. If anything, it can be perceived at times as poking fun of the original kinder’s overriding bleakness at many points, if not for the desire underneath to revisit themes that still held meaning to Parun. RE: was, again, re-interpretation in the most holistic sense. A personalized, introspective attempt–not in spite of, but because of, the humor it brings to itself–to look back on not just the work of the past, but to find the present within it. Finding the connections between both, like arranging an engine’s components, to come to a greater understanding of oneself.

Just one aspect of what made Parun’s late work remarkable, with the context of his earlier work, is how it affirms itself as process-driven art, made from derivative means. In the present, RPG Maker has gotten more respect as an engine capable of producing commercial successes, but that respect is not equivalent to its potential as tools for anyone to create art with. Even fellow hobbyists often hold themselves to standards that they perceive as properly up to par with commercial or “indie” games, excising what is currently considered “cliche,” “unoriginal,” or “embarrassing” as not artful enough. Yet Parun’s games offer a profound refutation against this conservative mindset on what art can’t be; by finding the personal within what is borrowed, by recycling objects to more clearly reveal histories and connotations, by putting faith in how the engine’s rules influence the result, he shows what art can be. That is to say, his work is one of the clearest proofs that if games aspire to poetry, it will not start with aesthetic prettiness and wholeness, but with the pen, paper, and written language being accessible to anyone. Parun wrote with an engine intended for amateur RPGs, and the red ink freshly bleeds through.

Further reading/watching:

- “Playing RPG Maker”? Amateur Game Design and Video Gaming” by Pierre-Yves Hurel (research into francophone amateur game making communities, the majority of interviews taken from RPG Maker developers)

- “DICTIONARY TO THE KNOWN WORLD” by Stephen Gillmurphy (creator of Space Funeral, talking about experiences in the 2000s RPG Maker scene in the West)

- RPG Maker - The Dream of the Engine | Preserving Worlds by Derek Murphy (features an interview with Gillmurphy talking about processes and tendencies of 00s development in the engine and archival of these games)

- NOMOIDA Reviews Heisei Pistol Show by NOMOIDA (for pointing to background on Parun and various things around his earlier, non-translated work)

special thanks to grace, phoenix, charlotte, cecy, pola, and leanne for their help in writing this